“Agriculture is the source of accumulation, from here we have to develop to an industrialized country and to get there we should think through, plan and put strategies in place. Unlike other countries which are forced to import raw materials, our country has all the raw materials necessary for developing our industries,” Mr. Kikwete was quoted saying.

This remains true, no matter how disturbing others will find it, and this is the state the sector is currently in.

When Mr. Peter Allum visited Tanzania two weeks ago, as part of an IMF Mission to Tanzania, he remarked, “Despite recent power shortages, Tanzania’s economy continues to grow strongly, expanding 6.3 percent in the first half of 2011.” On a similar note, the CIA World Fact Book says “Tanzania average 7% GDP growth per year between 2000 and 2008” was a result of “strong gold production and tourism,” and that “GDP growth in 2009-10 was a respectable 6% per year due to high gold prices and increased production.”

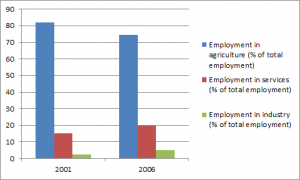

We hear a lot about similar GDP growth rhetorics. But what do they mean really? At worst, GDP growth rates are simply numbers that, as the case with Tanzania, may be accounted for by only one sector. Tanzania is essentially an agricultural country. (I may have read that the mining sector employees about/less than 2% of Tanzanians. Sorry, I could not find the exact figure.)

My previous post asked several questions, including one about why, with such a ‘respectable’ GDP growth, the country is still one of the poorest. This is an unsettling fact that prompts me to try and unveil the deadlock.

There is a nice story that everyone talks about. It is like a fairy tale, and it is the story about the Asian Tiger Economies. During the 1960s – 90s, these countries recorded extraordinary strides in economic growth. For example, Singapore, from 1970 – 93, grew at an average GDP growth rate of eight percent. In 1993, its per capita GDP had improved twenty-fold from US $900 in 1970!

Backed with a high human capital and high savings rate, the governments of the Asian miracles — Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, the Repulic of Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand — took an active role in shaping their economies. A high physical and human capital accumulation, and a market-oriented economy are attributable to the sustained economic wonders the world witnessed from the Asians. In fact, just like China is highly speculated to become the next super power, countries such as Japan were projected to overtake the US — that has not happened. We are yet to see whether China will become a super power due to a need for greater political command a world super-power needs, and a more efficiency in unit output per unit input. (China’s high population, only second to none, however, puts the analysis of its economic growth at a different perspective, not so comparable to Japan’s in the 1960s – 1970s.)

An emphasis on human capital accumulation through intensive investments in education, interacting with technology transfer that was obtained through a direct purchase, and educating large numbers of skilled engineers who would “absorb and adapt the most advanced technology,” has greatly contributed to the extraordinary East Asian growth. They also accepted foreign investment that came with new technology by creating conducive environments.

The theory of economic growth tells us that countries that win in the three areas of physical and human capital stock accumulation and technology, supported by high savings rate, will be set to see economic wonders. It would be a sad thing to refute this wisdom hard garnered by macroeconomists for more than one hundred years of research.

So, why don’t we just invest in capital accumulation — both physical and human — that will ultimately set us to an economic miracle? One simple answer is that it’s expensive and poor Tanzania is broke. Machines, the construction of roads, schools, employment of educators, improving or building new laboratories cost money. Another reason is that both the government and the society change with time. The question of evolving environment and government to the sustainability of growth is of the essence. As Joseph E. Stiglitz writes, a government that adapts its policies to suit the changing environment can learn from previous mistakes and its role changes adopting policies to “promote higher levels of technology and higher value-added industries.” Note the roles of the government portrayed in this paragraph: that of adaptibility and that of an investor.

To account for the economic growths of the East’s miracles, it can also be put forth that, this success came out of luck with individuals and profit-maximizing firms leading the way while the government remained auxiliary. Stiglitz puts similarly that “individuals had (perhaps rational) expectations concerning future rates of return; given those expectations, they determined their saving rate; meanwhile, profit-maximizing firms scoured the world looking for the best products and technologies to employ, given the costs of adjustment.”

The role of the government in an economy is highly debatable. There are those who draw motivation from Adam Smith’s “invincible hand,” there are those who prefer regulation and those who stand in between. Like socialist Russia in the 1950s that ultimately collapsed, countries that either followed strict government interventions in the market, free-marketeers or strictly planned their economies, failed. On the other hand, however, countries that saw economic wonders, writes Stiglitz, as if they had better learnt from the failures of socialist Russia, followed none of these systems. Borrowed from the theory of market failures, he writes, for a market to “yield efficient outcomes,” several conditions must be satisfied: “the absence of externalities and of public goods” and “presence of markets extending infinitely far into the future and covering all risks.” Meeting these conditions asks for a “well-defined, highly circumscribed role” of the government.

Even though market failures can sometimes not be prevented, Eastern countries managed to rescue their economies from collapsing by having the government have the following roles: “Ensure macroeconomic stability,” make “markets work more effectively by, for instance, regulating financial markets,” create “markets where they did not exist,” help “to direct investment to ensure that resources were deployed in ways that would enhance economic growth and stability,” and create “an atmosphere conducive to private investment” and “ensure political stability.”

A lot has been written about the Asian Tiger Economies. Given Tanzania’s current economy, I conceive of the following to be of import in achieving a deserving sustained growth that will see an exalted and equitable per capita GDP growth. First, we need “an Industrial Strategy for Tanzania.” Second, we need to pull off a modern financial services industry. Third, improve our domestic competitiveness (I discuss a synopsis here). Fourth, we need a GDP growth that accounts for the wealth of our people. Fifth, we need a better defined role of the government, and last but not least, we need to keep an eye on inequality. The order is impotent.

So, can we dare to unlock Tanzania’s economy? Can we have our own economic growth model? Can we replicate what has worked before? What role can our government play in all this?

Interesting! I would argue that the forces at play in the current situation of Tanzania’s economy is very much like the one some 45 years ago or so (with a few exceptions of course). The very bare bones of it : A broke country in need of making extensive and expensive investments in order to attain development, while maintaining equality (in terms of wealth distribution). Among the many solutions to this back then (like now) were :- 1) Borrow heavily from other countries and international institutions and make the investments, 2) Foreign direct investment 3) Grants/Gifts/Aid. The country was merely six years old (from independence) and the above options had a neo-colonialistic (I dont know if that is a word..but you get the idea) aura about them. i.e. there were strings attached to these options (structural adjustment programs etc). Enter the Arusha Declaration (which you should all read if you haven’t), which basically spelled out the government’s solution to this problem.

Most of the time we hear that the Arusha Declaration took away private businesses from their owners. But it was much much more than that (again…go and read it. Don’t take anyone’s word for it…not even mine). It essentially spelled out a strategic plan in which the country would engage in an industry where it had a competitive advantage (agriculture) and also took care to balance the distribution of wealth. Concurrently with this came free education and healthcare etc. Whether it worked or not is a question I leave for you to answer.

Fast forward some 45 years and here we are again, same problem. A broke country in need of making extensive and expensive investment in order to develop. The question is what exactly are we doing now? I see wishy washy investments in education, which will turn out to be more expensive than the monetary value we inject in this sector (read:poor quality of education = uneducated population). There are sectors in which we have a competitive advantage in (mining for instance). We have heavily emphasized Foreign investment here and as a result we aren’t getting what we could potentially get. The list goes on.

Speaking on developing an industrialized Tanzania: We MUST be strategic about this. It will be extremely stupid to start for instance a semiconductor manufacturing industry in Tanzania because we are at an extreme disadvantage when it comes to that i.e. the kind of investment we need to make it competitive (with say China) is astronomical. The industrial strategy should specifically define a target market (global? regional i.e east and southern Africa?) so that we know that whatever industry it is we’re setting up, we have a niche in the market (whatever that market is).

Please elaborate on “a modern financial services industry!”

How do you improve domestic competitiveness? This is an incredibly challenging problem given the influx of near-free products from giants like China that flood our markets day in day out. Yes, I just said that…because the Chinese are now competing us at a domestic level!

Role of government: I am not sure what it is doing. I need to read more on this perhaps.

Inequality: I doubt that we will ever come close to anything like the Arusha Declaration on this one…unless we have Arusha Declaration part deux????

Thats it, my two cents

@SL You know. There is a distance between poverty (at point A) and development (at point B). The two are joined by a line. It can be a steep line. It is impossible for one to simply find himself at B. One must start with a stride. He can walk, run, he may fall, and can find himself at point A again. It’s how one rebounds that counts and goes on with the journey. What sets us apart is how we approach B from A. One’s strategy determines how fast one gets there. There is no short-cut.

You note yourself that 50 years on, the same country finds itself in almost exactly the same situation, it’s broke, it has under-invested in human and capital stock. It has essentially fallen back to point A. So the question is, how do we go from here?

It’s a broke country. That we know. But ain’t there some way we can slowly accumulate our wealth guided by economic growth theory, maximizing where we clearly have a competitive advantage, like in agriculture or mining, agriculture gives us the money. We invest in technology, and training of engineers etc?

As of the issue with modern financial services industry, I think of a financial services industry that both accommodates for our domestic demands and meets international standards that can see even foreign investors invest in our banks. One that can trust and have the capability to loan us for our projects to grow. How can we use the money we invest through The National Social Security Fund (NSSF) for greater value-added projects that?

Let me give you an example. Citizens of country C, do not want to utilize part, P, of product X, because it’s not the best part. Companies that engage in this business make profit at home even without selling P. But like, any other firm, they want to maximize their profits. What they do is, they flood country D’s markets with P that can not be easily sold in C. They sell P inexpensively at the disadvantage of the locally produced X (including P but not necessarily separately). In country D, people can buy C’s P more cheaply than D’s P. People abandon all together the purchase of product X. The local business man closes down business as she can not compete. The business between C and D is legal and has been brought by globalization.

So my question to you all is, can we outsmart globalization? I have previously discussed a synopsis here at VFM.

Surely, I agree improving domestic competitiveness is a challenging task.

This is a fascinating discussion. Allow me to join in with the following thoughts:

1. We are NOT back to where we were 50 years ago, by any stretch of the imagination. For a start there are 46 million of us (compared to about 12 million in 1961). This creates all sorts of fantastic challenges and opportunities. Secondly, we are collectively, much more literate and far less ignorant than we were 50 years ago. Third we have many more choices in both what we consume (economically) and who we elect (politically) than we had 50 years ago.

2. I think part of the malaise and sense of dissatisfaction we feel with our ‘lot’ has to do with the undeniable sense of the responsibility that we must take for ourselves (individually). That responsibility comes with the expanded range of economic political and social choices that we face. We find it hard to resist the temptation to blame someone (the man/woman we elected or the boss who we chose to work for, or the cop we decided to bribe) for our less than satisfactory situation.

3. I like Stiglitz’s advice: adapt and invest. These do not come naturally to governments. Adaptability = flexibility (which sits at odds with bureaucracy). Investment = risk-taking since the future is unfathomanble (which sits at odds with the requirement for guaranteed outcomes that is almost enshrined in our accountability processes – a government dare not ‘lose’ money especially with the best of intentions).

4. So we have really one option left – to do the adapting and investing it ourselves as individuals and communities. To find the energy and imagination to, say stay in line in a traffic jam, to not throw the empty water bottle out of the daladala window, to politely state the glaringly obvious when our leaders err, to spend time with our (and other people’s kids) showing them simple values of honesty and fairplay, to drink one less for the road…I could go on, but you get the point.

Someone once said, ‘before kingdoms change, men must change’ Touche!

@Aidan, I very much agree with you in terms of there now being more choices economically and politically compared to 50 years ago. And I would also like to agree that we as a country need to adapt and invest. But on this latter point, I think adapting is easier than investing.

Tanzanians can adapt well and have been doing so for much longer than 50 years. It is in human nature to struggle to live, so we can expect to continue adapting.

Investing, however, is more complicated. I would argue that investing is more than just taking risk; it involves a mindset that is prepared to anticipate further risk, plan accordingly, and put resources to use so as to minimize future risk. All that involves coming into contact with the same bureacracy that re-inforces the same problems with economic development all of you have discussed so far.

Now bureaucracy is something we seem to treat as a side-effect, an extra “lump” of work you are expected to achieve if you have “all the papers in order”.

It is my argument that this seemingly non-challant part of the equation – the bureaucracy involved with investing – is actually the problem itself.

Why can’t a seventh grader with bad English grades compete for a grant from EWURA if he has the talent and willingness to work on a water pipeline project for his community?

What stops young secondary school graduates from going to study further when they have the intellectual capital to obtain scholarships and pursue their studies?

Why do officially registered businesses in Dar-es-Salaam have to show physical addresses for doing business; have we not caught up to the fact that not all businesses are involved in selling something from a physical location?

These three pseudo-examples all illustrate cases of desired investment met with bureaucratic roadblocks. I would also argue that these three examples highlight the agency of people who adapt, and yet who are met with systems of governance and economy that have not adapted to their needs.

So Stiglitz gives good advice; we should adapt and invest. But when it comes to investing, is bypassing the political and economic system possible? Is it even warranted? Or does it merely sidestep the problem in a way that leaves it there for others to experience tomorrow?

Zitto Kabwe, imagines Tanzania as 5th largest economy in Africa and largest in EAC!

http://zittokabwe.wordpress.com/2011/11/14/imagining-tanzania-5th-largest-economy-in-africa-and-largest-in-eac-by-2025/#comments