by Vincent Rwehumbiza

With its own words, in 1992, the Ministry of Water, Energy and Minerals reiterated that energy is needed to promote social and economic development for any developing nation like Tanzania. As is a need for any blueprint, the Tanzania energy policy had a long term perspective plan to increase the role of energy and water sector in revenue generation from 0.8% of the GDP in 1980 to 1.9% in 2000.

In the ‘80s, wood was the primary source of fuel while coal and natural gas were energy resources of high potential. Coal reserves were estimated to be about 1.2 million tons, while Songosongo and Mnazi Bay areas were projected to hold more than 29 cubic meters of high quality natural gas. Moreover, the country had a potential to produce 4.7 GW of hydropower electricity (HPE), but by 1992, only 10% of that capacity had been developed.

Tanzania National Electric Supply Company (TANESCO) had planned to increase power generation by installing stations at Pangani (60 MW), Lower Kihansi (162 MW), Upper Kihansi (62 MW), Masigira (80 MW), Rumakali (204 MW) and Mpanga (160 MW). Other potential sources were essentially at their technological infancy all over the world and comprised of biofuels, solar, wind, geothermal and ocean tides.

The energy policy planned to exploit the overly abundant sources of HPE, to develop and utilize coal, petroleum and natural gas resources, arrest wood fuel depletion by appropriate land management of development of efficient wood fuel stoves (refer to Tanzania Traditional Energy Development and Environment Organization plans) and develop efficient means to exploit forest and agricultural residues for production of energy for domestic usage. Last but not least and very important was to minimize energy costs through strengthening of the technologies for energy generation, transmission, distribution and firm supply infrastructure and promoting fair national pricing structure.

For years, Tanzania households and industries have experienced power rationing and severe blackouts, but still the country has six HPE generating stations that includes Kidatu (204 MW), Kihansi (180 MW), Mtera (80 MW), Pangani (68 MW), Hale (21 MW) and Nyumba ya Mungu (8 MW). Additionally, Ubungo gas plant produces 100 MW and a 100 MW from diesel at Tegeta. This makes a country total of about 761 MW, just 16.2% of the country’s potential of HPE.

Power generation by the stations has been marred by outdated infrastructure, poor management and investment policies.

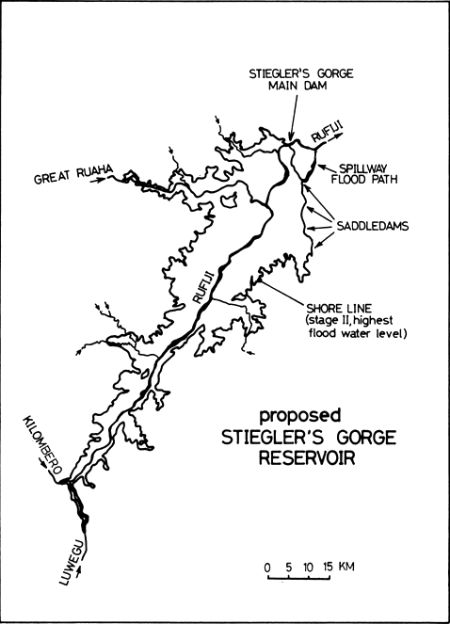

The biggest HPE project would have been the Stiegler’s Gorge Dam on the Rufiji River. Despite the anticipated social and ecological concerns after environmental impact assessment, the 2100 MW dam could have provided triple the existing energy output of the country. The project was planned between 1970 and 1980s by Norconsult, NORPLAN and NORAD; Norwegian organizations, but was halted mostly because of expensive engineering budget.

Given the total amount of funds that have been embezzled between 1970 and 2010 (estimated amount the subject of another day) — including large sums used to fund election campaigns and expensive vehicles for members of parliament and ministries — this project would have been complete. It is even possible that by now, rural electrification of all 8200 Tanzanian villages would have had occurred and our national grid connected to neighboring countries to trade the power surplus.

The downside on relying on HPE is severe droughts and currently due to climate change; it is a characteristic of most countries in the world. To alleviate this problem, investment into clean coal power plants will significantly reduce energy demands of Tanzania and power her industries.

In the U.S, a typical 500 MW coal plant burns 1.4 million tons of coal each year. Provided her yearly energy demands remain the same or other forms of energy generation pick pace, Tanzania can still afford two coal power plants that will quench some of her energy thirst for about 430 years!

In selling carbon credits as part of reduction of carbon footprint by any nation, a ton of emitted carbon dioxide costs about US$33.5 on the world market. Tanzania will be able to sell the remaining carbon credits to higher emitters of greenhouse gases. If the cost of building the power plant is US$1 billion, then we sell 5 million tons worth of carbon credits; we will afford to pay for the engineering costs in a 10 years and, in the long run, operation costs will be taken care of by selling the carbon credits and power. Thereafter, our country will start abandoning traditional sources of energy and shift to more renewable sources of energy to resurrect her industries and start manufacturing her high-end goods at low emission standards.

For a developing country like Tanzania, oil is too expensive to be used for power generation. To me, it seems that there is still a high potential if we exploit HPE and especially at the Stiegler’s gorge. Instead of pumping funds into many small projects, focusing all the resources into one big project would save a lot of time and money; and in the end deliver the end’s need.

Sometimes, I feel like most politicians assume that energy is not a basic need of our population. They mostly focus, or say talk about building roads, supplying water, building hospitals and schools, while forgetting that all these areas need to be powered for smooth operations.

Or, is it possible that some of the benefit from the lack of electricity? Do they have stakes in the petroleum firms that supply the diesel power sub-stations spread all over the country? Is it in the companies selling diesel power generators?

Lastly, local and foreign entrepreneurs want to invest in industrial development but power shortages pose a huge limitation in their investments and returns prospects. However, while we are thinking of exploiting available natural resources, we should also invest in research and development for renewable energy prospects in solar, wind, tide, nuclear and biofuels.

To some this seems like wishful thinking but I am positive that African governments can start funding their own researches and manufacturing by developing local talents. All I mostly see is that governments are sending their people to be trained on dying fields such as petroleum engineering, while research of the future are let to be exploited when they have already been established and extremely expensive. It is just that there seems to be no firm priorities and blueprints by the way the policies are made and governments run. Since it holds so many natural sources for energy generation, and electricity has never been and should not be a luxury; Tanzania should not fall behind because of lack of political will and failure to power its households and emerging industries.

V.R. kali ni kali!

But just a few things…

Do you have answers to the following?

What was the state of Tanzania industrial development by the time these HPE based projects were envisioned?

Because I am thinking the size of the market that could consume most of the electricity produced in order to pay off the investment might have not high enough. For example, developed countries have afforded to install coal based power generation plants because they have heavy and many industries that consume the largest share of the energy produced. Also the problem with producing energy for household consumptions, as would be the case with Tanzania, comes especially with load factors, costs of power transmission and energy losses (as a result of high voltage power transmission.)

In other words, suppose we assumed there was no embezzlement of the funds, would the Tanzanian market been able to support such expensive investments?

Lastly, if you can, can you answer these questions also taking into account the costs implied on a life-cycle basis?

My naive thinking is just that chances are high that people might have seen the projects rather impractical and just used the opportunity to embezzle the funds. Simple.

@ Bihemo…Nice and practical questions…I am mostly concerned about future investments. Perceiving the future as promising centered on the fact that the country is blessed with an abundance of raw materials and a clear development plan, industrial prowess is inevitable. The blueprint has to be conceived and its purpose properly exploited. Initial costs of any groundbreaking project are always impossible to comprehend, however, in the long run the investments start paying off. Basing our fine ideas and projects on fast profits will never change our societies for good. Whenever you build a road it doesn’t mean that you’ll be able to get the returns in a flash. The road will just set the precedent for other means of boosting the economy to flourish. In short, we should not wait for the industries to be built to start supplying power but the opposite. First, provide the necessary infrastructure then other challenges will be handled with time. Simply put, development is a process.

The issue is not the future, issues are

1. Who is to take us there?

2. Are we responsible for our own future?

3. How long shall we wait for realization of that future?