The following is an introductory blog post setting up the context of a recent Society for International Development (SID) Trend Monitor Report that analyzes an African Development Bank report titled “Africa in 50 Years Time: The Road Towards Inclusive Growth.” The Trend Monitor Report is initiative sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation with the aim of monitoring and analyzing key trends and patterns in the Greater Horn of Eastern Africa Region (Burundi, DR Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Puntland, Rwanda, Somalia, Somaliland, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda).

The African Development Bank (AfDB) was established in July 1966 with a major role of “contributing to the economic and social progress of its regional [African] members-individually and collectively.” The Bank has long been a major partner for many countries in Africa but the past decade has seen a significant resurgence of the Bank’s influence continentally and globally. Perhaps, it is no coincidence that as the global order shifts towards emerging markets the importance of an institution such as the AfDB has grown.

The AfDB has large resources. Its capital was increased to almost $100 billion in May 2010, an amount that represents almost 6% of the entire African continent’s GDP in 2010, or 1.3 times the size of the East African Community’s total GDP in 2010 of $75 billion.

The African Development Bank’s loan disbursements in East Africa (2010)

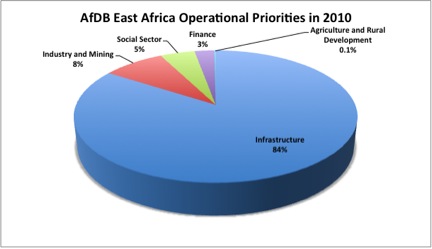

The loan and grant allocations by country in 2010 were as follows: Ethiopia ($345.6 million), Tanzania ($199.6 million), Kenya ($179.7 million), Rwanda ($63.3 million), Burundi ($52.5 million), Eritrea ($19.9 million), Sudan ($1.1 million), Comoros ($924,000), and Seychelles ($462,000). The AfDB’s loan and grant allocation to the Greater Horn of East Africa (GHEA) by sector in 2010 is noteworthy (see chart). Infrastructure projects received a total of $611.2 million or 84% of that year’s financing, while the agricultural and rural development sector received $1.2 million (0.1% of the 2010 allocation).

The Bank outlines specific drivers of change that will shape the continent in the next fifty years. These include structural changes in the economy such as Africa’s dependence on the West diminishing; trends in technology such as agricultural biotechnology and the ascent of renewable energy replacing conventional fuels and changes in the international economic game like new approaches to development aid. The report also discusses physical and human drivers of change relating to climate change/global warming and the demographic dividend respectively. These drivers of change will result in the following major outcomes:

- Urbanization will accelerate;

- Migration will increase;

- Agriculture is likely to decline in importance;

- Natural resources will remain important.

You can read the full report here, but here are some of our insights.

Eastern Africa’s halcyon days are on their way!

The report presents some very optimistic projections of Africa’s economic future. The projections for the region’s future are the most striking. The report shows that the economies of East Africa have grown faster than the Africa average since 2000. The future belongs to East Africa as its economic growth is projected to be faster than every other region in the continent.

GHEA’s share of Africa’s total GDP is projected to expand from just 11% (of $1.71 trillion) in 2010 to a very large 39% (of between $12.2 and $15.7 trillion) in 2060. East Africa’s share of the continent’s population will have expanded from 27% in 2010 to 32% in 2060. Per capita GDP is also anticipated to increase from the current $657 to between $6,000 and $7,000 in the next 50 years. Life expectancy is expected to increase and under-five mortality rates will decrease. We will not only live longer but will be able to see our children grow up and be successful.

The report’s implicit assumptions seem heroic

While the report does acknowledge some deep uncertainties going forward, these find little expression in its projections of the region’s future. There seems to be a strong but implicit assumption that the current trajectory can be extended far out into the future, without some radical resource-driven compromises being needed. The report seems to assume a high degree of GHEA’s adaptability and resilience to climate and conflict shocks.

Explicit references to climate change shocks are made. East Africa may experience a rise in average temperatures of 3.2°C by 2100, a sharp increase in the probability of extremely dry seasons; soil degradation could lead to a reduction in crop yields of up to 50% by 2060; and population growth and water withdrawal patterns could push large populations into water-stress situations. Curiously, the potential impact of these shocks is essentially invisible in the report’s projections.

The report is also mute on any potential security and conflict shocks on GHEA’s trajectory. The region continues to experience serious conflict situations in Somalia, Darfur, and even South Sudan where both internal tensions and those with Khartoum are simmering and may flare into deadly attacks. Interestingly, the report addresses the totality of the region’s conflict challenges in a nine-paragraph section towards the end that focuses almost exclusively on “the critical role that democracy needs to play in economic governance and the rapid and sustainable development of Africa.”

Where is the ‘inclusive’ growth?

While the report is sub-titled ‘The Road to Inclusive Growth’ the equity implications of growth projections receive surprisingly little explicit mention and analysis. A word search for references to “inequality, equity, inclusive, and redistribution” yields very few results. Apart from recognizing the mounting pressure on social cohesion posed by uneven growth patterns in the report’s introduction and four direct mentions of potential equity-enhancing policy choices, the report’s treatment of the inequality challenge, which is, arguably, at least as important as securing high levels of economic growth to 2060, is rather thin.

Other omissions were telling, although to be fair, such reports cannot cover everything. It was interesting that the only countries specifically mentioned were South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya and Rwanda, and that the African Union receives just one mention in the report. Might this be a subtle signal of the AU’s diminishing relevance to the continent in the coming decades? Might it be completely overshadowed by the AfDB as Africa’s intellectual, political and financial engine room? Time will tell.

Follow us on Twitter @SIDEastAfrica

From a recent Economist article about Eastern Africa’s energy-producing potential: “Tanzania has done well out of gold, earning record receipts of $2.1 billion last year, a 33% increase on 2010. It will do even better from gas.” Read more here.