In our quest to revive anecdotal experiences of men and women who shaped the history of the land that we now call Tanzania, we came across an interesting text about the life and times of the educator and civil-servant Martin Kayamba Mdumi, M.B.E (1891-1939). In its original form, we post here his autobiographical essay as it appears in Margery Perham’s book ‘Ten Africans‘ first published in 1936.

* * *

By Martin Kayamba, 1935

My Life and Work in East Africa

I was born on 2nd February, 1891, at Mbweni, Zanzibar. I am the first son of Hugh Peter Kayamba. He is one of the sons of Chief Mwelekwanyuma of Kilole, son of Kimweri Zanyumbai (Kimweri the Great) King of Wakilindi. The Wakilindi are a ruling clan, who ruled over the Wasambaa and other tribes in the coastal areas of Tanga prior to the German occupation of these countries. The first Mkilindi named Mbega came from the hills in the Handeni area. He was a famous hunter and through his hunting prowess and generosity was chosen by the Wasambaa to be their ruler. Chief Mwelekwanyuma was appointed by his father as Chief over the Wabondei and the Coastal section from Pangani to Vanga.

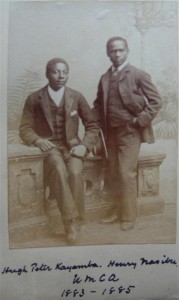

My father was born at Kilole Bondei, the seat of his father, about 1865. He was first a Mohammedan. My father joined the Universities Mission to Central Africa in 1877 and was educated at the U.M.C.A. Schools at Umba and Magila. He was sent to England in 1882 and was educated at Bloxham School, near Oxford. In 1885 he returned from England and became a teacher at St. Andrew’s College, U.M.C.A., Zanzibar. He married my mother, Faith Kalekabula, a teacher like himself, in 1890. My sister, Mary Elizabeth, was born on 23rd December, 1895. My father in 1892 was sent to the Bondei country to evangelize and was made a Reader. He resigned from the Mission in 1895 and joined the Government service at Mombasa as a clerk in the Uganda Rifles. He fought in the Mbaruk war and received a medal. My father worked for the British Government until 1926 and was last engaged as the Akida (Headman) of Mombo in the Usambara district.

I was baptized on the eighth day after my birth by Rev. Sir John Key at St. John’s Church, Mbweni. Miss C. D. M. Thackeray and Margaret Durham Mdoe were my godmothers, and Alfred Juma was my godfather. My mother was a very strict disciplinarian. She made me pray daily before I went to bed and when I woke up, and before and after taking meals. She taught me to give alms in church by giving me two pice every Sunday to put in the alms bag in church. She made a rule that I should be indoors at 6 p.m. and go to bed at 7 p.m. and wake up at 6 a.m. sharp. She used to wake up at 5 a.m. herself. She enforced the rule until I got married. She was very particular about my life and behaviour. She was very quick at chastising me. I received more thrashing from her than from my father. But she loved me dearly. She died on 28th August, 1912.

From 1895 to 1896 I was educated at the U.M.C.A. Boys’ School, Kilimani, Zanzibar, as a day boy, then I went to the Church Missionary Society School at Mombasa. In the school we were boys of various nationalities. There was one European boy, who was my great friend. There were also Indians, Arabs, Baluchis, Comorians and Swahilis, All lessons were taught in English. I was fortunate to pass all my examinations at the first sittings. In 1899 when I left Mombasa with my parents I had already reached the top form.

In 1899 my father resigned his service at Mombasa and went to Zanzibar, taking us with him. At Zanzibar I was sent to Kilimani School. Miss D. Mills was in charge of the school, and Miss E. Clutterbuck was the schoolmistress, assisted by African teachers. Bishop F. Weston (he was a priest at the time) was our Chaplain. The discipline at Kilimani was very strict indeed, and I must confess both Miss Clutterbuck and Miss Stevens were sterner than any of my headmasters. Boys used to get whippings every day. Sometimes mothers of the boys quarrelled with them for whippping their children or detaining them in close confinement without food and water. The Chaplain also was very strict. From the Life of Bishop Weston [Frank, Bishop of Zanzibar -, by the Rev. H. Maynard Smith, S.P.C.K., page 58]: ‘From time to time he examined the secular work of the school and sometimes he was asked to inflict corporal punishment. This he did with as much vigour as all else. . . .’ The boys were more afraid of the schoolmistress at Kilimani than they were afterwards of their headmaster and masters at Kiungani College. At Kilimani I was again fortunate in my lessons and in one year I got to the top class.

In 1901 my father went to the Bondei country and took us with him. I was sent to the U.M.C.A. school at Magila. I was there for about six months. In 1902 my father returned with us to Zanzibar. Bishop F. Weston, who was at the time the Principal of the Kiungani College, asked my father to send me to Kiungani College as my friends in England were paying for my education in the U.M.C.A. My friends were Mesdames C. N. Goldring and Weston. On 1st February, 1902, I joined Kiungani College. I was placed in the III Class. In the July 1902 examination I passed and was promoted to II Class. In the December 1902 examination I passed and was promoted to I Class. My age was then 12 years. Being a small boy, I was not made a teacher.

The discipline was very strict at Kiungani. Bishop Weston was very strict and good to the boys. He treated us like his own children. The food that was supplied to the boys during his time was exceptionally good. The welfare of the boys was his first and foremost consideration. He used to tell us, ‘do not want to be called a miser.’ If the cook did not cook our food well, he ordered it to be cast away and he cycled to the town to get us bread and relish. In school one could never wish a better teacher. He taught all his subjects clearly and lucidly. In discipline he was very rigid. He never cautioned an offender without whipping him. Every evening after our dinner, guilty boys were watching with anxiety who would be called first to receive some thrashing. It was a rule that after the second school bell had rung there should be a complete silence. One day, just after the second school bell had gone a mango fell down and I impulsively shouted to a teacher, ‘A mango has fallen down!’ The Bishop was walking towards my direction going to the classroom, and he heard me shouting. He instantly ordered me to go to his room at 12 noon after school time. When I got there all to my grief and unexpectation, he gave me ten with a cane. I expected to be warned as this was my first offence in the college, besides that I was a stranger, but I was whipped. Boys who failed in examinations always received thrashing as their prize, and this was done every month because we had monthly test examinations.

In the book of the Life of Bishop Weston, page 45, he writes to a friend:

We are as a training school far more efficient than we were a year ago; and I have hopes and schemes for a still greater development and improvement. I introduced one new feature into the prize giving which fairly staggered the school. After declaring that my Majesty was pleased to approve of much that the boys had done, I proceeded to inform my subjects that there were some whom the examination had proved to be mere idlers and wasters. For them also I had reserved prizes of a different sort which would be distributed later in the day! Oh, that you had seen the faces of the slackers! So I left them from 4 p.m. until after dinner in awful horror and dread expectation. At 8.15 I was about to ring for the first victim, when in came a lazy youth to explain why his marks were few. As I had no designs on him I cheered him up. Later, ping! my bell rang, and up rushed a real prize-winner, all agog to know who would be called! “Call Petro,” says I, and downstairs he ran into the arms of an expectant throng. Up came Petro, fearful and sad. One boy, one brute, one cane and six of the very best. “Call Martin” [another boy called by the same name as myself he was his godson]. Enter my godson. One godson, one godfather, one cane and six of the very best. “Call Antonio.” Enter the fat boy of the school. One fat boy, one thin headmaster, one thinner cane and six of the very best. “Call Jack!” Enter the harum-scarum of the school with many excuses. One protestant, one pope, one cane and six of the very best. Meanwhile below were several sinking hearts, which only beat normally when Jack was heard to go weeping to bed, calling no one to take his place. And these new kind of prizes I have promised shall be given after each examination, much to the annoyance of many small kids.

The discipline which Bishop Weston instilled in the boys of the college was of real value to them in after life. It was the intention of Bishop Weston that I should eventually work as a Mission teacher. Personally I did not think that this was my vocation. My mother was taking a great deal of pains to bring me up in a real Christian way. My father was keen that I should receive the best education available in our Mission schools. When I was at home my father always gave me some, homework and not infrequently I got a severe lashing from him for making mistakes in my lessons. One advantage I had in my school days both my parents were teachers and took a great deal of interest in my education.

In December 1904 I was made a teacher. As I did not like the work I did not associate much with my fellow teachers. Of course, most of them were much older than myself. I was strictly instructed not to mix up much with the boys. One day I took a boy off his duties in contravention of the order and I was severely reprimanded by the Acting Principal. I angrily offered to resign the post of a teacher, and that same evening I was reduced to an ordinary schoolboy. Bishop Weston was in England on leave when I was reduced in rank. On his return from leave he tried his very best to persuade me to take up the rank of a teacher again, but I refused and selected to leave the College to work as a clerk outside.

In February 1906 I left Kiungani College and went to my father at Mombasa. There were not many settlers in Kenya in those days. There were a good number of European commercial firms at Mombasa. The hinterland was not so much improved as it is today. The tribes were living in peaceful occupation of their land. My father put me in the Telegraph Department to be trained as a telegraphist. After a month I was ordered to proceed to Voi Station to work in the post office there. My mother refused because she thought I was too young to be left alone, so I had to resign from the post office. My father then got me into the Public Works Department to be trained as a draughtsman. On 1st June, 1906, 1 joined the Drawing Office under Mr, Dodd, Architect, and was trained as a tracer. I made a good progress in this work and Mr. Dodd was very good to me. After six months I was transferred to the Store Department to work under the Chief Storekeeper, Mr. C. W. Gregory, who had just arrived from South Africa. My work there was good and Mr. Gregory made me in charge of outside stores.

After some few months I resigned and started my own business. My mother and godmother were against my doing trading business. When I started the business my mother was in Zanzibar, and when she returned she objected to my doing the business as I was very young. In the end I had to give in and I ceased trading. On 6th September, 1907, 1 was re-engaged in the Public Works Department as assistant store clerk in the Executive Engineer’s Store at Mombasa. Mr. McGregor Ross, who was the Director of the Public Works Department, was very kind to the African Staff and took a great deal of interest in their work and welfare. He made personal visits to sick African employees and arranged for the doctor to go and see them in their houses.

On 11th February, 1908, I married Mazy Syble, a teacher of the Girls’ School, U.M.C.A., Mbweni. My wife was a pupil-teacher of the girls’ boarding school and was herself a boarder. I first knew her when she came from Pemba to the Girls’ School, Mbweni. She was a very small girl at the time. I met her again at a wedding at Mbweni and engaged myself to her in 1905. On January 9th I was transferred to the Public Works Store, Nyeri, as a store clerk. On the same day after my departure a daughter was born to us, named Constance Faith Mary.

At Nyeri I had to act as sub-storekeeper for six months as two European sub-storekeepers, as a result of ill health and old age, died a few days after their arrival. On the arrival of the third European storekeeper I was transferred to Fort Hall Store as a clerk in charge of Fort Hall Public Works Department Station. I worked there for a year. Mr. C. C. Cresswell, the Executive Engineer of the P.W.D. there, was very kind to me. He treated me very well and proposed to build me a nice house. At Fort Hall he built me a nice little corrugated iron sheet round house, the first of its kind in that part of the country. He trusted me in my work of responsibility. He gave me the charge of the Fort Hall store and P.W.D. Station there. On 29th December, 1910, I was stationed at Nairobi as tools and plants clerk in charge in the Executive Engineer’s office. On 25th February, 1911, we got a son named Hugh Godfrey.

On 15th April, 1911, I resigned. As the Director of P.W.D. stated in my certificate, ‘I was becoming a very useful clerk when I elected to resign for the second time.’ I was dissatisfied with the salary I was getting at the time, which was not equivalent to the responsible duty I was discharging when in Nyeri, Fort Hall and Nairobi. The Asiatic staff who were doing the same kind of work or less were paid better than the African staff. I proceeded to Zanzibar, where I was employed as a private tutor to two European Government officials. In August 1911 I secured an employment in the Public Works Department, Uganda, as a workshops clerk. I left my wife and children with my parents at Mombasa and proceeded to Entebbe, Uganda, alone. The Uganda natives have their own native Government under the Kabaka or King; they have their own native Parliament and Treasury and courts, it is one of the most advanced native Governments in Africa.

A few days after my arrival in Uganda I got shocking news by telegram that my wife died at Mombasa. My heart was entirely broken and, although I liked my work in Uganda very much, yet I soon realized I would not be able to remain in that country alone after such tragic news. I had left my wife in a very good health at Mombasa and she took me to the railway station at Mombasa to see me off. I was really staggered by the sudden news of her death. She died eleven days after my arrival in Uganda.

In the workshops there were many Baganda apprentices, trained as carpenters and blacksmiths. I was very happy amongst them, and made several best friends. Prince Joseph of Kampala was a great friend of mine and so was Sosene Muinda, who is now a big chief near Kampala. I was afterwards transferred to the Store Department as a store clerk. On the departure of the Chief Storekeeper to England on leave, I acted as issuing clerk.

A friend of mine, Mr. J. Walker, a native of Sierra Leone, persuaded me to join the International Correspondence School of London. I chose the commercial course, for which I had to pay about 20 in instalments. I passed several subjects and the lessons were of immense benefit to me. I am sorry to say, owing to the intervention of war in 1914, I was cut off from communication and could not complete my course.

On 28th August, 1912, my mother died at Mombasa. It became impossible for me to remain any longer in Uganda owing to these two deaths of those very dear to me. I had already got an employment in the Government School, Zanzibar. On 20th September I resigned my post in the P.W.D. Entebbe and returned to Zanzibar via Mombasa. I was sorry to leave my service because the Director of Public Works was very much interested in my progress. I had worked under him at Mombasa and Nyeri and he knew me since I started my work in the Drawing Department at Mombasa. He arranged to put me as an apprentice in the Drawing Section. He asked me to write to him about work again as soon as I had finished mourning at home. I am sorry I could not do it.

In the Government School, Zanzibar, there were over two hundred boys of various nationalities. The principal nationalities were Indians, Arabs and Swahilis. The headmaster was a Parseej under him in the English classes was a Goan, and I was the third teacher. There were also several Arabic teachers under the Arabic schoolmaster. It is wonderful that this conglomeration of nationalities and teachers was always friendly. The school was and still is a very important one in Zanzibar. Boys belonging to the royal family and high Arab families were being educated in this school. As I am a Christian and this was a purely Mohammedan school, I was required not to teach the Christian religion or talk about it in the school. It is surprising that in this school there never were religious controversies even though it was the centre of Arabic and Koranic culture. There was no distinction among us except of rank, and Arab teachers never shunned me. We were always very friendly indeed. I cannot understand why this is seldom possible outside such an environment.

A certain teacher belonged to a noble Arab family, and had been educated at Beirut in a Roman Catholic College his father had spent a considerable amount of money for his education. One day he told me that in the Beirut College he used to go to the college chapel. I at once stopped him talking about this as it was against the school order given to me. Another day as I was going to a classroom to teach I met him on the steps, and he said to me that he liked the Christian religion. I was thunderstruck and really I was on the horns of a dilemma. To prevent him from talking about Christ and his religion was to act against my religion, a soldier of the Church Militant would never retreat from such a situation, yet to encourage him to follow Christ was to break the school law. The only course remaining to me was to walk away without saying a word, and this I did. Whether he read what was written on my face or not, I do not know; but in the evening on my return from the football game I was struck to find all my furniture in one of my rooms had been removed to another room and new furniture had been substituted. I asked my servant who had done it. Suddenly to my great surprise I saw the teacher entering the room. I asked him what was the matter. He replied that he had fallen out with his father because he refused to go to the mosque to pray. I was perturbed; his father was a great friend of mine and I found it rather difficult to reconcile the situation. I could not send him away because I did not know where he would go to. There was no alternative but to force him to go to the mosque to pray, as he was ordered by his father. So I made it clear to him that I would not have him in my house unless he went to pray in the mosque, and asked his father for pardon. He argued. The next day I went to see his father over the matter. He was evidently very sorry to see me. The news of his son’s stay at my house had already reached him. He took me to his inner room and told me he was very sorry and much upset about his son. He was surprised that I, who was a great friend of certain big Arabs and was much trusted by them to enter their houses and be introduced to their families, could break faith with them by enticing his son to become a Christian. I explained all the circumstances to him as they had occurred and undertook to return his son to him. I told him I had sheltered his son because I was afraid he would go astray.

On my return home I spoke strongly to the teacher and made him return to his father. This brought me peace. I think I was right in the step I took. I could never make myself believe that a boy who was so unthankful to his father could make a good Christian. What actuated him on the spur of the moment to adopt a Christian faith was obscure to me. On the other hand I thought that if he really meant to become a Christian my action would not deter him. On this I was light, because he never talked about it to me again. I had had several experiences of the sort before of people who imagined they were called to become Christians and eventually discarded the religion after gaining their worldly aims.

The schoolboys were good, and we had a variety of types; the discipline was very strict. For lashing an Indian truant the headmaster was sued in the court by the father of the boy. But the Government defended the headmaster. A circular was issued to parents after that, to the effect that schoolboys were subject to school discipline and punishment and parents who wished their boys to remain in the school had to agree to this. My time in the school was always full. I was in charge of the football game; and had to coach, at their homes, Arab boys who were backward in their lessons. I also had to give Swahili lessons to Europeans after school hours. I liked the schoolwork and had many friends in the school and outside. My boys were getting on well.

On 9th January, 1914, I resigned the post in the Government School and went to the Bondei country to visit my relations and if possible do some trading. I thought I needed some more money to better my prospects. I got a passport from the German Consul at Zanzibar for myself and my daughter, and sailed to Tanga. At Handeni I took out a trading licence for which I was charged the 60 rupee fee paid by Indian traders for a similar business. The German District Commissioner at Handeni, after inspecting my certificates of service, said to me I was an intelligent man and should therefore pay the same fee as Indians. Natives paid 56 rupees for the same kind of trading license. For the bigger license I was asked to pay 100 rupees, other natives paid 60 rupees.

I made two trips in the interior, trading. On my second trip, whilst returning to Muheza, in the train at Korogwe I heard a rumour that there was war between the British and the Germans. Natives were talking about it. It was 2nd of August, 1914. On my arrival I hurried to the U.M.C.A. Station at Magila and reported the matter to my friend Mr. Russell. He did not believe me and said it was impossible for the British and the Germans to fight because they were friends and relations. I replied that I thought there was something in the rumour, and returned home. Then I heard the German troops were already on the move and Rev. Spanton, the Principal of Kiungani College, Zanzibar, who had come with his college boys from Zanzibar on vacation leave, had been arrested by Captain Hering and sent to Tanga under escort.

This was the beginning of troubles. The natives were much excited to hear about the occurrence of war between the British and the Germans. Some of them thought they had prophesied its occurrence. Why and how they thought so it is difficult to explain, but there were some who even predicted its outbreak that year. The news of its outbreak did not appear to be very astonishing and in a few days it was a commonplace talk. I could not get my way to Zanzibar or Mombasa, where my father was, and this was really bad for me and my daughter. Brother John (Rev. Williams), who had gone to Tanga to try and get a dhow for Zanzibar, was unsuccessful. All roads to Kenya had been closed. German troops were already at Tanga and Moshi. I then heard that English missionaries and planters had been arrested and escorted to Morogoro for internment. Rev. Keates and a few mission ladies were left at Magila Mission Station. My daughter was very ill at the time. She had a bad sore foot. I took her to Magila Mission for treatment. A false allegation was fabricated against Rev. Keates that he was signalling to the British men-of-war near Tanga from a hill near Magila by means of fire. It was the beginning of the persecution of the African Christians belonging to the U.M.C.A. I found my safety was jeopardized. Rev. Keates, mission ladies and African teachers of Magila were escorted to Morogoro, Kilimatinde and Tabora.

On 12th January, 1915, my turn came; I was sitting at the farm of my relation when I was called to the village, which was about fifteen miles inland from Tanga. Jumbe Omari of Umba, who was my nurse when I was a small boy, came to see me with a message from Akida Sengenge of Ngomeni; I was required by the District Commissioner at Muheza. We walked there together. The District Commissioner asked me what I was doing and if I intended going anywhere. I replied I was trading and produced my license, which he took from me. I said I had no intention of proceeding anywhere. He asked me where I had come from and when. I replied I came from Zanzibar, and delivered my passport from the German Consul, Zanzibar. I was informed afterwards that certain persons had reported to him that I was a spy and had come into the country one month before the outbreak of the war from the Zanzibar Government. This was disproved by my passport from the German Consul, Zanzibar. He asked me if I was a British subject and could speak English. I replied in the affirmative. He then said I would be sent up country to stay there till the end of the war as I might create trouble in the place. I said I was not going to make any trouble and I had my trade property apart from my personal property, and what would happen to it? He said I would get it after the war, but I had to be sent up country to stay there till the war was over. I was then escorted to the prison. As I had only 20 rupees with me I asked my relations to send me another 80 rupees, in two instalments of 50 rupees and 50 rupees because I was afraid the German African soldiers might rob it from me if they knew I had money. They brought me 50 rupees and before I received the second instalment I was handcuffed with another Bondei Christian, named Geldert Mhina, and was escorted to Handeni. At the Muheza Station the German Assistant District Officer of Tanga abused us and said we would surely be shot because we were passing news to the British.

At Korogwe we had the most terrible time. As soon as we got there, it was about 2 p.m., we were put in a prison gang and despatched to carry sand till the evening. We used to work with criminals from 4 p.m. till 11 p.m. From 8 p.m. to 11 p.m. we carried ammunition boxes from the train to the Police Station. We had our meal only once a day, at 4 p.m. 5 the meal consisted of boiled maize. We were kept with criminals and treated as criminals. After six days we were escorted to Handeni together with the wounded British soldiers of the Lancashire Rifles who had been captured in the battle of Tanga. The British soldiers were carried in hammocks by the native prisoners of war. On the way the British soldiers were well treated. We were joined by the Korogwe English missionaries, including Bishop Birley and Brother John, with African teachers of the U.M.C.A. We marched together to Handeni. There we met in prison over one hundred African teachers of the U.M.C.A. and Rev. Canon Petro Limo, an old African priest. These were afterwards sent to Kondoa Irangi, where they were brutally treated in prison. Some of them died as the result of the most atrocious treatment meted out to them by the German officer of Kondoa Irangi and his African prison warders.

Our gang was sent to Kimamba. Some of us were made to carry the loads and hammocks of the English missionaries. I was fortunate to obtain a job of safari cook. I got myself engaged in this work in order to save myself from carrying loads and hammocks for nearly eleven days. I had never carried loads before in my life. I knew nothing about cooking as I had never done this work in my life, but I had to make the best of it. Having tasted European food while at Kiungani College and having often been dining with Miss Thackeray, etc., I had to form some idea as to how this food was cooked. It was a difficult job. For two days the cook of the German officer was doing the whole cooking and I was watching him. On the third day I was ordered to do everything myself. I do not know how I managed it, but somehow or other I made some sort of food which was fairly eatable. I remember one day I boiled three ox-tongues for three hours and yet they were as hard as a bone. I did not know the trick of getting them properly boiled. But to my surprise they were passed as eatable. I sometimes wondered if the food cooked by me could be eaten by anybody else other than missionaries. They probably knew I was not a cook and made concessions accordingly. I must have caused them bad stomachs, but I did not hear of any complaints. If I had cooked for the German officer I would surely have received some knocking for bad cooking.

When we got to Kimamba my work ceased. I contracted an acute dysentery on the way and at Kimamba my condition was worse. But I was cured by a German doctor at Kimamba. On our way to Kimamba the German African soldiers who were escorting us were treating our gang very badly. They made us run and lashed the stragglers. Bishop Birley very often had to rebuke them for this. It was the road of the Cross. At Kimamba we entrained for Tabora and the English missionaries detrained for Mpwapwa. On our arrival at Tabora Railway Station we were despatched to the Prisoners of War Camp. There we found Indian soldiers who had been captured at Tanga and Jassini, about two hundred of them, and some African teachers of the U.M.C. A. who had been sent there before us. These are the teachers who were together with Rev. Keates. They related to us that when they got to Tabora they were sent to gaol and kept with criminals. They were so very harshly treated that they thought not one of them would survive. They were made to hoe from morning to evening without lifting their backs, and whenever they tried to do so they were severely flogged. They were all in chains and slept with chains round their necks. They did everything in chains. At last their condition was so bad that they had to choose between life and death.

One day when they were returning from their daily toil they met the German Chief Secretary on the way with his wife. Apparently his wife was French. The leader pulled the whole chain gang and approached the German Chief Secretary in spite of the threats from their escort. The Chief Secretary asked them what was the matter with them, and they told him they were brought from Muheza by the Government and they did not know why they were not tried but were put in gaol with criminals and treated worse than criminals. He said he would go into the matter and they would hear from him later. The result was they were transferred to the Prisoners of War Camp and were promised a better treatment. They saved us and everybody who came after them. The camp was guarded by German African soldiers. There was a separate camp for European prisoners of war. First we were detailed to carry building stones from a certain hill to the European camp, about a distance of two miles. We were made to run all the way with stones on our heads, an African soldier in charge was lashing those who were behind. He had a special order from the German officer to drive us and lash us. This order was given in our presence before we started the day’s work.

The time was really terrible for us and I remember a day when I was so exhausted that I was on the point of fainting. We had our meal once a day in the evening and had to cook it ourselves after we had been exhaustively fatigued and were very hungry. What frightened us most was the news that a Greek had been sentenced to death for having signalled to the British troops at Moshi by means of fire. He was shot. We were very dejected and could not tell what our fate would be. During the first days we were not supplied with relish and had to live on bare cassava. We had to sleep on the open ground. Our drinking water was filthy. Buckets which were used for W.C. were afterwards used for our drinking water. It was not surprising when dysentery of the worst kind broke out in the camp. One-third of the Indian soldiers and about one-sixth of the native prisoners perished of it. On certain days we had to bury as many as six persons in one day. There was not a day that we did not bury someone. It was a camp of death.

A German doctor was appointed to the camp and a hospital was built near the camp. It was always full. The diet was then Altered and two German officers were appointed in charge of our camp. These gentlemen were very good to us. I was first made one of the headmen of the camp. My duties were to supervise my fellow prisoners at work and in camp. Headmen had more than this to do. It fell to our lot to represent the grievances of the African prisoners to the Camp authorities. I was afterwards made a head mason. I learnt this work in camp. We had to build a brick house for German officers, and as my work was good I was soon promoted to the rank of head mason. In the camp Geldart, my mate, and myself were in charge of camp construction work, and we built a very nice camp. Our clothes were worn out and we were not supplied with clothes or blankets by the German authorities. We had to contrive some means of obtaining clothing. Our food was brought in American! bags, and we had to turn the bags into shirts and shorts. I was then transferred to the camp hospital as a hospital assistant. There I worked with Dr. Mohammedin and Dr. Kudrat Ali of the Indian Kashmir Rifles. They were both good men. Dr. Mohammedin was always helping his people very much. Dr. Moesta, a German Medical Officer in charge of the native hospital in town and our camp hospital, was exceptionally good. He did all he could to help the patients and poor people and’ I often saw him spending his own money to help them. He treated us very nicely indeed. Another German medical officer who was formerly in the man-of-war Kordgsberg was also very good.

I was afterwards transferred with another African prisoner, Samwil Msumi, to the native hospital in town. My work was to look after patients in the wards and give them medicines and to help in the operation room. Samwil Msumi was doing microscopic work colouring blood preparations, etc., for the doctor to examine by microscope. Dr. Moesta took the trouble to train us to examine germs found in blood, etc., of patients by microscope and to diagnose diseases. We could do this work eventually. He gave us a good medical training and we became very useful to him in the hospital. He often worked from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. and was never tired. He visited each in-patient twice a day and examined personally every patient who came to the hospital for treatment. He could speak several European languages. Every one in our camp liked him. The condition in our camp was ameliorated and the diet was improved. The work for prisoners was not so exacting as before. The buildings in our camp had to be extended by us, as we were getting more prisoners in the camp and the accommodation was insufficient.

I was very anxious to see my daughter, whom I had left at Magila with a bad foot. There was no sign of the ending of the war, and we did not know what our fate would be. We first thought the war would take only three or six months to end, or at most three years. Periodically we got news about the war through the Africans. It was wonderful how Africans could pass from mouth to mouth news about the war in Europe, which was perfectly correct. The news travelled so quickly that even cable and wireless could hardly compete. We heard about the approach to Paris by the German troops, the joining of the Turks on the side of the Germans, the death of Lord Kitchener, the arrival of General Smuts and his troops at Mombasa. Although the defeats of the German troops were kept strictly secret, they were soon known to the prisoners in the camp. How and by what means the news was obtained it was difficult to tell. Some of us were incredulous until the news was proved to be true on our release.

When the Belgian troops were near Tabora, some of the African prisoners were taken as porters for the German troops. In the hospital I met a British doctor who had been captured 5 1 was ordered to take him to our camp for a visit. On the way I had a long conversation with him and I explained to him our position. I have seen a book written by him about the war in which he mentioned our meeting at Tabora. A German missionary was working in the hospital and was very kind. He took me one day into the doctor’s room when no one was there and told me that he was very sorry that two friendly Christian nations were fighting against themselves and that we African Christians were persecuted by a Christian power. He then started weeping and said he hoped God would soon bring all this to an end. We then parted. He was always kind and good to every one and never said a harsh word. He was very sorry for Archdeacon Woodward of the U.M.C.A., who was at the time in the European Prisoners’ Camp at Tabora. It was arranged for the Roman Catholic priest to visit us once a week and preach to us, and we had to go to the Catholic church on Sundays. Bishop Leonard of the Catholic Mission, Tabora, was very good to us. Afterwards Archdeacon Birley (the present Bishop) was allowed to come to our camp under escort to hear our confession. On the first day the German European soldier who escorted him to the camp wanted to hear what the African Christians confessed to the Archdeacon. He bade him that they should speak audibly for him to hear. Evidently he suspected that they were telling him something in connection with the war or he was passing war news to them. The Archdeacon retorted that he could not divulge what was said to him in confession, what he heard in confession was sealed and couldn’t be given out to anybody.

So such was our state in prison. We had neither bodily nor spiritual peace. On a certain occasion on Sunday after we left church we went to the market, and whilst returning to the camp with our escort we passed the European camp where the Commandant of the Prison Camps had this office. He saw us passing and asked us where we had been. The escort replied that we were coming from the market. He said he would come to the camp to hear the case. Directly we got to the camp we reported the matter to the officer in charge of the camp. He said we should not have passed near the European camp. He had no objection to our going to the market, but he knew the Commandant was not good. We did not know that the Commandant would find fault with our going to the market. In a moment the Commandant arrived at the camp and saw a prisoner peeping through the hospital window. He ordered him to be given five lashes. We were all brought before him and he inquired as to who originated the plan of our going to the market. There was some dispute between two prisoners, each one of them contending that the other started the plan. The Commandant could not waste more time over it, and in fact he did not mind who got the punishment; it was sufficient to him that someone got it. So the last speaker of the two was ordered to be given fifteen lashes. The Abyssinian Sergeant administered the strokes. When he got to three strokes the Commandant thought he didn’t lay the strokes firmly, so he ordered that a strong man should do it, and a cruel Indian prisoner snatched the hippo stick from the sergeant and hit the prisoner with all his might.

When the Belgians were near Tabora, Dr. Moesta, who was in charge of the Civil, and Prisoners of War, Hospitals at Tabora, got permission from the Governor for me and Samwil Msumi to remain with him in the hospital when our prison mates were removed from Tabora to an unknown destination. On Tuesday, September 19th, the Belgians entered Tabora at 12 noon. In the morning Dr. Moesta asked me to select twelve of my friends to remain with me at the hospital. It was a special favour, but most difficult to put into action for the simple reason that I had many friends in the camp, and to select some and leave the others to suffer was the worst betrayal of friendship. Those who were to be removed from Tabora courted death at every minute and to let one be removed was tantamount to condemning him to death. I did what was humanly possible in such matters. One of my friends whom I could not save was actually crying when he was leaving me for the bush. No sooner had they left than Dr. Moesta came to me again and said to me I could select as many of my friends as I wished to remain with me in the hospital. Alas! It was too late, I could not do it as they had already gone.

African teachers were left behind with the European missionaries. We could not work in the hospital as it was contemplated because the Belgian African soldiers burnt the hospital near the camp and looted the property of the patients. They also burnt our camp. They pillaged some of the native properties and took away with them some of the wives and daughters of the natives. It was unsafe for women to walk about. They committed several atrocities in the native town. The whole town was thrown into chaos. We had to go to where the English missionaries stayed. I saw Dr. Moesta the next day and I told him I could not work in the hospital owing to the state of affairs at that time. The whole town was in chaos. Business was disorganized and the native inhabitants were panic stricken. Food was commandeered by the Belgian military authorities. It was unsafe for natives to walk about in the town. The Belgian native soldiers were a terror to the native inhabitants of the town. Wherever the Belgian troops passed in the country there was desolation and privation.

On the 1st October, 1916, I left Tabora with the European missionaries and African teachers to go to Kisumu, where we were kindly received by the Kavirondo Christians. This excellent reception was arranged by Bishop Willis of Uganda. From Kisumu we went to Nairobi. Here we were well received by the British Red Cross Staff. At Nairobi I suddenly became very ill indeed. My old friends took me to their house and nursed me until I was well again. They nearly -gave up all hopes of my recovery. I then travelled to Mombasa and was very glad to see my father, sister, brother-in-law and son.

When I reached Tanga I applied for work at the Political Office. The District Political Officer engaged me as interpreter as from 1st February, 1917. I had to work for the Police and in Court. There was much work in the Political and Police Offices at the time because the country was not quite settled up from the effects of the war. However, the work was good.

On 6th October I married pupil-teacher Dorothy Mary Mnubi of the Mbweni Girls’ School, Zanzibar. Her parents are Zanzibarians and her home is Zanzibar. Her father, mother and eldest sister had been to England and received some education there.

In 1918 we had to work to raise money for the British Red Cross. Europeans, Arabs, Asiatics and natives all contributed handsomely to the fund. I hired the Tanga Cinema and raised 573 rupees for the fund. My wife put to auction one native dish cover which was worth a shilling and it fetched 40 rupees. A feat was arranged and several thousands of rupees were collected for the Red Cross. Tanga was animated by the Red Cross work and over 55,000 rupees was collected for the fund. The Africans were very keen on helping and I can certainly say that Tanga was never so happy as in those days. The natives liked very much the new regime because forced labour, flogging and oppression from German native soldiers had gone and they were anticipating a rule of justice and fair play for all subjects. The work in the Political Office was good and the officers were doing their best to help the Africans by every conceivable means. We had the arduous work of collecting porters and detecting the deserters from the military. In 1918 I was transferred to the Political Office as interpreter and clerk. In 1919 I was promoted to a correspondence clerk and typist in place of an Indian clerk. On 15th August, 1919 I got a daughter named Louisa Beatrice Mary.

On llth November, 1918, it was Armistice Day. Everyone was very glad to see the end of the great war was drawing nigh. From 19th to 21st July, 1919, we held Peace Celebrations. A big feast and sports were made to celebrate the occasion. There was a great rejoicing everywhere on that great day.

On 1st September, 1925, P. E. Mitchell, Esq., M.C., Acting Senior Commissioner at Tanga, started to run the District Office with entirely African staff. I was made head clerk. The work was rather difficult in the beginning because most of the clerks were new to the work. It was due to the efforts of Messrs. P. E. Mitchell and F. W. C. Morgans that the whole scheme became a success. In the beginning we always had to work from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. without an interval for midday meal. We were bent to make the scheme a success. We were the first Africans in the whole of East Africa including Kenya, Uganda and Zanzibar to be trusted with such a responsible work. The morale of the African clerks was exceptionally good and every clerk was scrupulously honest. Our office collected 40,000 per annum, and the whole of the accounting for this money was done by a few African clerks, who had in addition to attend to administrative and clerical work. It has been proved that Africans can do the work if they are only patiently controlled.

We built our own Club building. It was the centre of much progress socially and in sports. Several distinguished officers visited our Club and gave donations. One gave us a football ground which the Club had to clear and put in order. The Club started the football game in Tanga and now there are several African football teams. It was the intention of the Club to start a library in the Club building, but owing to lack of funds this scheme was impracticable. The late Bishop F. Weston was invited to the Club and was very pleased to see something at last had been done which he never thought he would see, and that was Christians and Mohammedans, Africans and Arabs joining together as members of the association, and all being very friendly. Religion is the matter for the heart and must come first, but it does not prevent members of one religious community from combining with members of another religious community. I firmly believe that Africans will never progress well unless they realize the necessity for unity. A great deal of our progress rests with us. We cannot move if we do not wish to move together.

In 1928 I was appointed as a member of the Provincial Committee on African Education. In 1929 1 was appointed a member of the Advisory Committee on African Education for the Territory. I have much advocated education for girls. In Africa, where the great majority of the Africans are uneducated, the education for girls is very important indeed and will help considerably the progress of the boys’ education. The mother is the guide of her children. If she is educated there will be very few children who will not go to school and the hygiene at home will be thoroughly observed. Childbirth and child welfare will be better understood at home. African homes will be improved. We lack at present the co-operation of African women in social affairs and education. Their influence is very great and precious, but it has not been used, for lack of female education.

In church, I was appointed churchwarden from 1917. Our church was too small for the congregation and we decided to extend it. African Christians contributed fairly well towards the fund in proportion to their income, and our church has now been enlarged. The condition of Christians in Tanga is different to that of up-country Christians. We have a floating population and conditions are somewhat difficult, but on the whole we are progressing. The population of Tanga town is about 7,000 natives of mixed tribes. For most of them Tanga is not their home, they have migrated from the hinterland to Tanga in search of work, and return to their homes up country as soon as they have made some money; some of them come to Tanga periodically for work and return to their homes during the cultivation and planting season. Tanga, being a town, offers the Christians many temptations which they are not likely to meet with in their own tribal homes.

Early in 1931 I was appointed as a witness from Tanganyika to the Joint Parliamentary Committee on East Africa. The story of my visit to England forms the next part of this autobiography.

* * *

To be continued…

This text can be found in full at the Internet Archive Project.

Related post:

So many small and detailed stories in here! I found three aspects particularly interesting:

First, Mr. Kayamba’s ability to become a teacher at age 14. Talk about career advancement.

Second, his exchanges with so many different cultures (Swahili, German, Indian, “Arab”, Belgian and British). We have read about cosmopolitan systems from the distant past (1000, 2000 even 4000 years ago) but this is documentary evidence of a similar system right here at home from more than 100 years ago.

Third, this is also evidence of how secular and religious education can be and were dispensed in the same institutions. Very interesting stuff… looking forward to reading the next installment.

On a completely different note, we should probably learn how to write “minor” details down in our lives for future generations to read, as we are reading of Mr. Kayamba’s life now (names, dates, posts, anecdotes, etc.)

What an excerpt…Looking forward to similar stories of cycles of birth, triumphs and tribulations in precolonial and colonial Tanganyika/Tanzania…

I especially liked how Mr. Kayamba advocated for education of women/girls…very emancipated for a man of his time…He kept talking about his daughter, wife and mother throughout the excerpt…

I am very humble and blessed to know the story of my great great grandfather. Louisa is my grandmother (my late mum’s mother). Thank you for publishing this. Be blessed