Interview by Mieke van Dixhoorn, April 2012

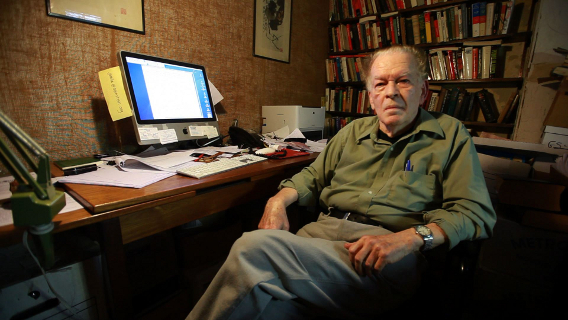

How do you effectively depose a dictator? Political Scientist Gene Sharp (83) preaches nonviolent action. After seeing the movie: ‘How to start a revolution’ during the Movies that Matter Festival, it becomes clear that Sharp has influenced many revolutionary movements all over the world including some during the Arab Spring. Some say one of his books: ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy’ is the bible to nonviolent resisters; according to some government officials it is a bomb. Vice Versa watched the movie, read the book and had a conversation with Gene Sharp’s protégé: Jamila Raqib.

According to Jamila Raqib the most common reaction to the movie ‘How to start a revolution’ is: ‘I cannot believe I’ve never heard of Gene Sharp.’ And that is totally OK, says Raqib, because: ‘The people who really depended on his work, usually found his work. When asked to describe what he does at the start of the film, Sharp explains: ‘I try to understand the nature and potential of nonviolent forms of struggle to undermine dictatorships.’

Sharp is the world’s leading expert on nonviolent revolutions. From Dictatorship to Democracy, Sharp’s most read book, is the basis for the movie. It is a guide for resisters to achieve a successful nonviolent revolution. In the final pages of the book, one finds a list of 198 nonviolent weapons and methods that can be used by the revolutionaries. Sharp wants to show that there is a realistic alternative to war. Sharp and Raqib continue to work on their research out of their office in the Einstein Institute, which is now residing on the ground floor of Sharps home in Boston because of a lack in financing.

Sharp wrote From Dictatorship to Democracy at the request of U Tin Maung Win, a democrat from Burma. Through ex-general Bob Helvey, Sharp came in contact with the Burmese resistance. They were in desperate need for the information Sharp had to offer. They asked him to write a book in understandable language. Because Sharp did not feel he knew enough about the Burmese situation he decided to write the book in general terms, but based on more than forty years of scientific research.

Essence

The movie starts with a quote from Sharp in the center of the screen: ‘Dictators are never as strong as they tell you they are. People are never as weak as they think they are.’ This is the essence of the movie and Sharps book. Gene Sharp argues that every form of leadership in a country is dependent on the population. ‘Even a totalitarian dictator is dependent on the society he rules.’

Sharp identifies power sources like legitimacy, support from the population and institutions and access to resources. When it is clear what the regime needs to survive, your mission as resisters becomes obvious, Sharp writes. Every form of political power depends on the people. When you decrease the support and obedience of the people, the regime will topple. It is extremely important that the resistance is nonviolent. This makes it harder to fight for the regime. When you choose violence, you choose to fight the battle on a field where the dictator has an enormous advantage.

Discovery

In the opening minutes of the movie, the viewer reads ‘Use colors and symbols’, number 18 from the list of nonviolent weapons. What follows are several examples where this advice is followed. Take for instance the Orange revolution in Ukraine and the uprising in Iran after the reelection of Ahmandinejad when everyone wore green. The next lesson ‘Use English signs’ is also followed by examples from Egypt and Iran: ‘Where is my vote?’ As audience you discover as it were the same thing as director Ruaridh Arrow did.

As a newspaper journalist, Arrow reported on a lot of the so-called ‘color’ revolutions like the ones in Yugoslavia (2000), Georgia (2003) and Ukraine (2005). He noticed that in these revolutions everyone was using similar tactics. At first he considered that the CIA was involved, because it seemed as if someone was directing these revolutions. But after talking with the leaders of several groups, it was not the CIA but Gene Sharp that was mentioned. When Arrow again saw the same non-violent tactics in 2009 with the ‘Green Revolution’ in Iran, he decided to do some more research. At that time the only image he could find of Gene Sharp on the Internet was a propaganda movie that is dispersed by the Iranian government, in which Sharp is accused of being a member of the CIA. Ruaridh Arrow was curious to find out more about Sharps history, so he contacted the Einstein Institute in Boston.

‘At first it was Arrows intention to document Genes story and do just straight interviews with him,’ Raqib explains. ‘But when the Arab Spring started, the movie changed and he added the conversations with the revolutionaries.’ Both Raqib and Sharp had little to do with the movie, which worried them. Raqib: ‘We were afraid the film would say: Here is what you need to do, here is what others have done, now go do it [start a revolution, ed.]. That would be extremely dangerous. The amount of information required is much more detailed and nuanced.’ At the premiere of the movie, Raqib and Sharp were able to heave a sigh of relief.

Revolutionaries

In the final motion picture there are case studies, including Burma, Serbia, Ukraine, Egypt and Syria. Several revolutionaries told Arrow their story and how Gene Sharp has influenced them. Srdja Popovic, leader of the civic movement ‘Otpor!’ (Resistance!) from Serbia, explains for instance how he learned about Sharps work through Bob Helvey. ‘I was ashamed I had never heard about it before. Seeing all the knowledge of how power operates and all the things we would have had to learn the hard way through experience, written down systematically in one place was quite an amazing thing. Popovic: ‘We knew that the majority of the people were against Milosovic. All we had to do was recognize each other.’ The leader of Otpor gives the viewer an example of their nonviolent actions: ‘Our numbers were falling because we were demonstrating every day in the harsh winter. So we thought: let’s go home and make noise from our balcony. You could hear it everywhere and we did it during the state news. So we showed them: we don’t watch your crap.’

The audience also meets Ausama Monajed from Syria. He actually visits the Einstein Institution to ask the experts for advice. However, Sharp and Raqib have always refused to talk about actual cases. They always stay on general terms because they don’t want it to seem like they are organizing the revolutions. Raqib: ‘We are a scientific institution.’ Most of the time Sharp and Raqib do not even know who they are talking to. Even with email a lot of revolutionaries work with aliases. ‘We don’t know for sure who was using our work in Egypt,’ Jamila explains.

The sensitivity of Sharps work also makes financing it very difficult. Most lawyers of development organizations call their bosses back when they consider supporting the Einstein institute, Raqib tells me. It is extremely complicated for organizations to support Sharp without seeming to want to topple a government, instead of building a strong civil society.

Circulation

From Dictatorship to Democracy has been translated into more than 35 languages and is dispersed over every continent, except Antartica. In many countries with dictatorial governments it has become infamous. In Burma, someone carrying this 130-page book will be sentenced to a seven-year stay in prison. The two independent bookstores in Moscow who dared sell the book, almost immediately burned down in the same night.

Sharp and Raqib themselves do not have much to do with how their work spreads. They only ordered some of the many translations now available. The experts do however value consultation with the ones who are translating the work on their own initiative. Raqib: ‘We ask them to follow certain guidelines. We’d rather have no translation than a bad translation. Otherwise terrible things could happen.’

With the invention of the Internet, the spreading of Sharps work has become a lot easier. The number of downloads of the text from the Einstein institute website has grown exponentially. The work is copied by other websites so fast that it has become impossible to track it around the world. ‘Maybe we don’t want to know,’ Raqib says. The Internet has made the spreading of Sharps words easier, but she is worried that it has also made people less careful. She takes out a version of ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy’ with a false cover that someone drew to hide the true content of the text and says: ‘People were always really creative.’ On the cover a wolf is surrounded by angry sheep and they are closing in on him.

Most Prominent

The most prominent and talked-about revolution right now is going on in Syria. Raqib expects the regime will resort to violence. ‘The Syrian regime has been desperately seeking a militarization of the conflict so that they can more easily crush the uprising.’ The struggle in Syria is still overwhelmingly nonviolent though; therefore the revolutionaries can still win. The nonviolent way gives them the opportunity to make smart choices. Raqib: ‘Resistance methods can be chosen that minimize direct confrontation and casualties, such as holding stay-at-home strikes instead of marching toward machine guns.’

International military intervention would be a mistake according to Jamila. A big part of the success of nonviolent struggle is, also according to Sharp, that people accomplish their goal on their own. ‘Moreover, says Raqib, recent studies show that international military intervention waged in the name of protecting civilians actually increase violence in the short term and increase the duration of civil wars.’

Personal

What revolutionary movement catches Raqibs eye at the moment? ‘I am going to give you a biased answer: Afghanistan.’ Raqib, Afghan-born, then outlines the very violent history of the country. ‘I think the people are sick of the violence and the war.’ But she has hope; there is a group that is studying Sharps work right now. Raqib: ‘So positive!’

It surprises Raqib that there is nothing in the international press about a big meeting that was held recently in the Eastern part of Afghanistan: a Jirga. These meetings are an old custom, at which leaders from all over the country come together to talk about their problems and come up with solutions. About five thousand people came to this particular Jirga. The Pashtun passed around their translation of From Dictatorship to Democracy. Raqib: ‘According to my information there were international journalists present. But not a word about it! The resistance you see is not just against the Taliban, but also against the occupation: the NATO.

People look at Afghanistan as a security problem. Outsiders don’t know what to do with the country anymore. Well, perhaps people themselves can end it and fix their own problems. How about that?

Thanks for letting us publish your work, Mieke!

Questions from Vijana FM:

- What do you think about non violent revolutions?

- How can young people promote revolutions of their own in nonviolent ways?

- When is change necessary?

Further reading: