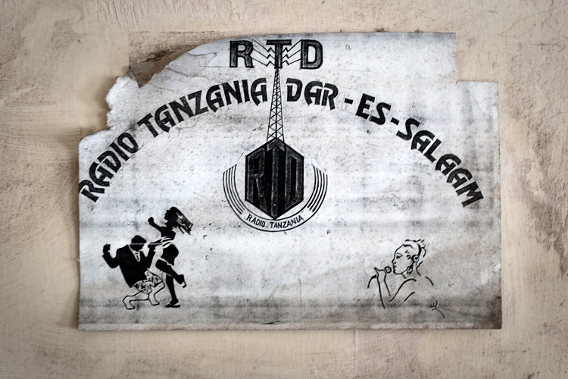

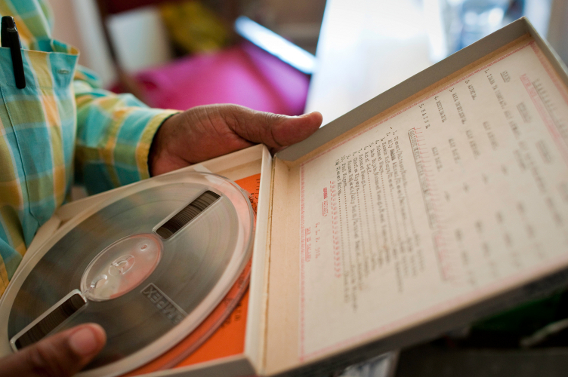

A few months ago, the Tanzania Heritage Project embarked on a mission to revive Radio Tanzania’s music archives. These archives, stored in the form of magnetic tapes, date from the 1960s to the 1980s. Until now, these rare audio gems remained on tape, thus out of reach for anyone growing up in a world of digital media. The Tanzania Heritage Project’s work “will include providing high-quality equipment for the transfer of the music and training Tanzanian employees/interns to perform the bulk of the digitization” in the near future. Vijana FM corresponded with THP’s Executive Director Rebecca Corey, who was kind to tell us more about the project.

1. Why is it important to preserve the past’s music?

The beautiful thing about music is that it is a universal language. I once heard a Zimbabwean proverb that says, “If you can talk, you can sing. If you can walk, you can dance.” It is easy to fall into the trap of believing that people from different cultures or even neighborhoods are different than you, and therefore somehow less deserving of kindness or empathy or attention. But music unites people. When a collection of music like the Radio Tanzania Dar-es-Salaam archive is in danger of being lost forever because it’s trapped in a decaying, obsolete medium, you see people from all over the world come together with a common goal: preservation. It’s because we understand that art is essential to the human experience, and that a nation’s musical history is priceless and irreplaceable. We can imagine a world without this music, and we know that’s not a place we want to be.

Right now, culture and technology seem to change at the speed of light. The songs on the radio cycle through every few weeks. A video will go “viral” on YouTube, be seen a few million times, and then be forgotten a few days later. The latest and greatest phones or iPods are out for just six months or less before they are replaced by the next version, and the old versions end up in the ever-growing trashpile of cultural refuse, yesterday’s discarded hits. Unique musical styles and scenes are increasingly overcome by the pervasive tide of Western culture. All of this change and innovation is exciting, but its implications are a little scary.

Art is not static– it is always dynamic and evolving– and to understand where we are going it’s important to remember and understand where we have been. Because culture is constantly in flux, it’s a little misleading to talk about “cultural preservation” as though there were a time in the past when music was stuck or unchanging. What we need to focus on is understanding the evolution of music and culture over time, in conversation with the past, present, and future at any given moment. Preserving music from the past isn’t just so we can capture something we’re nostalgic about– it’s so we can continue to grow and move forward.

The music and broadcast archives at Radio Tanzania Dar-es-Salaam are essentially an ethnomusicological history of Tanzania, showing the nation’s development from independence to its transition to a free-market economy in the 1980’s. You can trace– in the lyrical content, instrumentation, and style of the music– the various political and economic forces at play at any given moment. You can even see the Tanzanians of the early-Independence era taking an interest in preserving the ngoma indigenous performances of rural Tanzania as a part of reclaiming a cultural heritage that had been oppressed by colonialism. Now, that material and the music from the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s is in need of preservation and revitalization. Today, there’s a great interest in understanding how Nyerere’s Ujamaa (African Socialist) policy was articulated by the government, understood by the people, and negotiated through cultural expressions like popular music, which is why the muziki wa dansi collection in the archive is of such particular significance. The bands, while owned and managed by parastatal institutions and censored by government bureaucrats, still breathed life into their works and played an integral role in the evolution of Tanzanian national identity and unification.

Music is a repository for social, cultural and historical knowledge. Stories, values, social rules, taboos, allegories, and even details of important historical events are passed from person-to-person, and from generation-to-generation, through songs. Historically, music has been a force for social change, protest, and moral education, and it continues to be an incredibly powerful force for reflecting the realities and even shaping the discourse of modern life. Preservation is vital to ensuring that those lessons live on and that the fabric of culture remains rich and vibrant, rather than homogenous or unrooted in time or place.

2. How else do you think can we preserve artwork, such that it can be referred to or even developed by more people later?

I believe that the way artwork is preserved and shared is at the brink of a revolution. Digital storage technology, music and image sharing, and collaborative artwork have all seen drastic innovations and improvements in the last few years, especially as social media becomes ever more powerful and omnipresent. Preservation is certainly just the first step in the process of cultural revitalization. Once a collection is physically preserved, then it needs to be digitized, then catalogued and described, then curated and explained in its cultural and historical context, and then–and here’s where it gets really exciting and interesting– it can be truly shared and participated in. I’m not sure if this term has been widely used, but I think the next big thing in the field is what you could call “participatory preservation.” At least, that is what the Tanzania Heritage Project envisions: a way for individuals to take part in the process of preservation, from tagging and metadata, to sharing the tracks that speak the most to them with their networks, to “sampling” from preserved works, to creating new artistic pieces that are inspired by and informed by preserved works and can be presented in conversation with the art to which it responds.

In my opinion, this is the most promising opportunity that the digital age creates: the ability to juxtapose items from all over the world and throughout history in one universally accessible place–breaking down the barriers of space and time–to show the progression of an idea or artistic expression, and then allowing individuals to engage with it in a meaningful and lasting way.

3. Who becomes the owner of the digitized contents once they are produced? Does this change over time?

The conversation around copyright and intellectual property is one of the most pressing subjects of debate in the digital age, and has interesting ramifications for our project. Some experts in audiovisual preservation and the music industry see digitization of endangered collections as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it increases access to the material and makes it easier to research, catalogue, and preserve, but on the other hand it opens up the material to possible digitial theft, misuse, improper citation, or piracy. The archivist has to weigh these advantages and disadvantages when deciding whether to digitize a collection.

In copyright law, there are both mechanical rights (who owns the physical recording?) and publishing rights (who owns the right to perform, play, or sell the song contained on the physical recording?)– and sometimes the lines between who owns what rights can be very blurry, especially in the absence of written legal contracts. Though the Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation claims full legal rights to the material recorded in the Radio Tanzania studios, the Tanzania Heritage Project seeks to ensure that artists will finally be compensated for their works and that all ethical standards of licensing are followed.

In Tanzania, the rights of artists last for their lifetime, plus 50 years after their passing (according to the Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Act of 1999). It is the responsibility of the archivist to make all possible attempts to locate the copyright holder to get permission to use or share the work. Our goal is to weigh the economic interests of the artists with our desire and mission to share the music with as many people as possible. We hope that both artists and the Tanzanian government will agree with us that the more listeners we can get, the better. Even if the music is shared for free or low-cost online, Tanzania will benefit by seeing increased revenues from tourism, the live music industry, advertisement on websites, tv channels, or radio stations that play the music, and the intangible but no-less-real value of a strong cultural milieu.

Our core commitment, though, is to Tanzanian artists and we promise to respect their rights to the songs they created.

4. Will the archives continue to archive new styles of music as they develop?

The Tanzania Heritage Project will create a platform to celebrate music from the past and to allow a new generation of artists to be inspired and educated by it. As new musical styles develop in conversation with the digitized archival music, we will provide a place to show those new styles next to the old ones that influenced them.

Luckily, though, contemporary artists are recording digitally these days, so we don’t have to worry about their work being trapped on an obsolete format like the magnetic tape reel-to-reels of Radio Tanzania Dar-es-Salaam. Preservation is definitely an ongoing discussion because technology is developing and progressing so quickly, so someday the current recording and storage systems we’re using now will also become out-dated. It’s important to stay attuned to all of the technological developments so you can ensure that the music you are playing or listening to will continue to be accessible to you in the future.

5. How can young people help in this archiving process?

Young people can help in our project to revive the Radio Tanzania archives by joining the discussion online via our Facebook and Twitter pages (@RadioTanzania), and spreading awareness about our work. We want to hear from people about their personal experiences and memories of Zilipendwa music or the RTD station while they were growing up. We want to hear about what music people are listening to today, and how it relates to the music of the past. We want to hear from young artists whose work has been inspired by music they listened to as children.

We also need volunteers interested in translating lyrics from Kiswahili into English and other languages. People interested in volunteering should email us at info (at) tanzaniaheritageproject (dot) org.

Basically, we want to leverage the power of social media and word-of-mouth to ensure that everyone in Tanzania and around East Africa know what we’re doing. Then, individuals can contribute by donating to our mobile money accounts, and they can help shape our organization by telling us what features, artists, and discussions they would like to see on our website, Tanzaniaheritageproject.org.

Our slogan is “Pamoja kwa muziki.” Together for the music. We can’t do this without the help and support of the community, and we hope you all will join us.

Thank you for your insights, Rebecca! The Tanzania Heritage Project accepts donations through the following channels:

- PayPal

- Tigo Pesa # 0655 542 939

- Airtel Money # 0687 542 939

Other related links

- Tanzania Heritage Project website

- THP on Facebook

- THP on Twitter

- Tanzania radio station websites

- Five questions with Jonathan Kalan

- Jonathan Kalan photography

- More Vijana FM interviews

I learned a lot from your response to Question 3 – thanks! About this – “Our goal is to weigh the economic interests of the artists with our desire and mission to share the music with as many people as possible” – are you in touch with the artists whose records are going to be digitized? Any chance of doing similar interviews in the local TZ press? I think this medium (social/Internet media) is very akin to young folk outside the country, but the older generations (who were the young folk back in the 60s and 80s) probably just listen to radio or read newspapers now. Could be potential areas to garner more support for this great project, especially from the artists themselves. All the best!

Hi Jack,

Thanks for your comment!

We are in touch with a few musicians whose work is contained in the archives– notably John Kitime, Anania Ngolia, and King Kiki– and we hope to track down as many as humanly possible. In order for this music to be released, we will likely HAVE to find them, or at least their descendants. This is another way we hope to be able to leverage the community– to help put us in tough with the hundreds of musicians whose work is stored in the vaults of RTD.

As to your second question, we are definitely hoping to do interviews with the local TZ press. We had one small story in the Citizen already, and hope to see another in Mwananchi and BBC Swahili soon. You are very right that many of the older generation will not hear about the project if we only have media coverage online. Our supporters can help us in that regard as well, by letting their local stations/channels/papers know about us and suggest that they cover us!

Thanks again!

Rebecca

A very interesting article. Music has always been something that has been a sense of inspiration for me. I see myself listening to old Beatles songs and truly get a sense of what it was like to be in the 60s not just from what it says in the actual songs but just from emotion that pervade all of theirs songs. I can see how they are repositories of historical knowledge.

My family is actually from India and I see my parents and grandparents listening to a lot of old Indian songs which are sung in Hindi. Note that I know very little to no Hindi what so ever but I can still listen to those songs and be touched just by the feelings of the singer. In this way music is really a universal which has the ability to touch people no matter which language it’s sung in. The importance in what you guys are doing may be overlooked at times, but you guys really are making a difference by doing things like this.