The following is an introductory blog post setting up the context of a recent Greater Horn of East Africa (GHEA) Outlook report published by the Society for International Development. Read the full report on the region’s infrastructure deficit here. To read other SID newsletters and learn more about the Rockefeller Foundation’s Searchlight Program click here.

One hour, that is how long it takes to travel 4km in Nairobi during the peak of rush hour. Everyone is aware of the incessant traffic jams in Nairobi to the point where it has become part of the daily lifestyle of living and working in Kenya. Kampala and Dar es Salaam have not been spared the advancing state of vehicular gridlock on their roads.

The quality of East Africa’s transport infrastructure has always been an issue, but with the economic growth surge of the past ten years, it is now threatening East Africa’s capacity to handle the influx of people and goods, and may be slowing the region’s economic growth. By 2015, the capacity of handling the traffic forecasted in the port of Dar es Salaam would be exceeded. The congestion at the port of Mombasa risks an economic slowdown due to time consumption. It takes an estimated twelve hours by truck to get from Mombasa to Busia (the Kenya-Uganda) border, and that is if traffic is not an impediment.

There is a renewed sense of urgency amongst the political leadership and private sector to handle the infrastructure crisis, how much of this is rhetoric over substance remains to be seen, but it is quite clear that the status quo is unsustainable. The region has responded to the infrastructure deficit with the development of transport corridors.

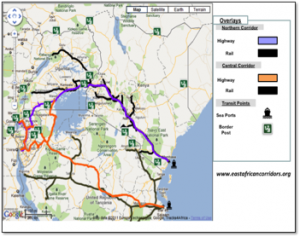

The region’s three corridors

The Transport Corridors consist of the Northern and Central Corridors, which serve nine countries (Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Sudan and Djibouti). It covers approximately 5,000km trunk roads of various grades, 4,500km of rail line, 17 major border crossings and 2 major seaports (Mombasa and Dar es Salaam).

The Northern Corridor has the port of Mombasa in Kenya serving as the lifeline for Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi; it ends in the city of Bujumbura. It needs $1.87 billion in financing to make it fully functional. The Central Corridor has the port of Dar es Salaam serving as a lifeline of imports, exports and trade for Rwanda, Burundi and the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The Central Corridor currently needs an investment of $1.67 billion to revamp the infrastructure and make it fully functional.

Another major project is the proposed Lamu Corridor linking Kenya with South Sudan and Ethiopia. It is known as the Lamu Port-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET). It seeks to provide South Sudan and Ethiopia with an accessible way to the Indian Ocean. This ambitious corridor will include a port as well as rail and road transportation hubs linking Lamu to the interior. In addition, a critical aspect of the Lamu Corridor is the proposed South Sudan-Lamu pipeline which is expected to provide an alternative crude oil transportation network.

The east-west corridors ignore north-south opportunities

But who are the corridors for? Clearly the main reason for the East African corridors is to boost economic growth by lowering the costs of moving goods and thereby increasing the volume of trade. This suggests that the corridors are for the benefit of the regional economies and enhancing the relationship with international markets. The corridor map clearly shows the east-west direction of the corridors, linking the Indian Ocean ports with the population centers that are the markets for imported goods. The agricultural, mineral and other resources found in the region’s interior form the bulk of the region’s exports to the rest of the world.

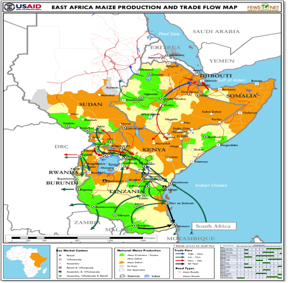

What is particularly striking is the relegation of intra-regional trade to a seemingly distant second place in the priority list despite the rhetoric and pronouncements made about its importance. There is scant mention of creating or upgrading the routes to linking the food surplus regions in southern and western Tanzania the food-deficit regions in northern Kenya, northern Uganda, Somalia and Ethiopia. The maize production and trade flow map overleaf is a striking illustration of where the major surplus food production occurs (green in the south) and where the deficit areas are to be found (orange in the north). Contrast this with the east-west direction of the northern and central corridors. The proverbial money and the mouth do not seem to be converging. The much-vaunted growth in the trade of goods produced in the region for internal consumption seems to be left to happen almost on its own.

Informal trade will face an ‘efficiency shock’

Informal cross border trade accounts for a significant portion of overall regional trade. According to the permanent secretary in the Kenyan Ministry of Trade, “informal cross border trade currently accounts for about 30% to 60% of all inter-regional trade. These informal traders thrive from the status quo but it is hard to determine the consequences of implementing the corridors. Improving the transport corridors is expected to reduce the costs of road transport by up to 25% in the northern corridor and 11% in the central corridor. The time to ship goods by road will reduce by up to a third in the north and half in the central corridors. These cost and time reductions represent a significant and positive ‘efficiency shock’ to the region’s economy.

Certainly, informal trade will benefit from the improved transport infrastructure and the cost saving that it represents. To the extent that informal trade crosses national boundaries at designated border posts, the seven new one-stop border posts that are being built across the East African community partner states also ought to have a beneficial effect by combining two countries’ formalities in a single space and eliminating the duplication of procedures. However, it is clear that informal trading has thrived in part because of logistical inefficiencies that have allowed it to serve markets and consumers that more formal distribution channels do not reach. The improved transport corridors will reduce this constraint and may lead to a greater formalization of cross border trade.

However, the net effect of formalization could be ambiguous. For it to be beneficial at the individual level, any increase in the cost of formalization to the trader (administration processes, fees, taxes) must be more than outweighed by an increase in business. But it is not clear that small traders will be able to capture the cost savings represented by improved transport infrastructure. Larger traders with deep pockets and distribution networks could edge out their weaker competitors by translating cost savings into lower retail prices for the final consumer. So, while systemic efficiency is good at the aggregate level, it may be painful at the level of the small and/or informal trader who for various reasons may find themselves unable to compete.

Thanks for the links to the report and Searchlight! As the end of your post mentions, I think it’s important to consider small traders working in populated urban settlements across East Africa.

Many traders benefit from local intra-city and inter-city transport, which also means travelers like buying goods from them. Rather than replacing frequent local stops with occasional transport hubs, I would like to see a network of local+express transport services, for transport of both people and goods.

“EA to save $1bn on vehicle load control” (The Citizen): http://thecitizen.co.tz/news/4-national-news/19825-ea-to-save-1bn-on-vehicle-load-control.html